The Black and White Hero

Luciano Spinosi was born in Rome on May 9, 1950. At the age of ten, he suffered a broken leg when he was hit by a car. «I went from being left-footed to right-footed,» he often recounts. He recovered and joined Tevere Roma, playing in the Fourth Series (Serie D). Luciano quickly earned a reputation for being a tough tackler and, despite eating copiously, remained thin, earning the nickname «Er Secco der Villaggio» (The Skinny Guy from the Village). He maintained, «I was always perceived as a hard tackler, but that wasn`t entirely accurate. Certainly, I made strong tackles, but I never injured anyone deliberately and, crucially, I was never sent off for a bad foul.»

Early Career and Roma Debut

In the summer of 1967, he made a significant leap from Serie D to the top flight, joining Roma. He made his Serie A debut as an eighteen-year-old. «It was a Monday, and coach Pugliese came to me, telling me that the following Sunday, against Torino, I would be in the starting lineup. He told me to stay calm and, perhaps to soothe my nerves, predicted I would even score. I privately thought this was highly improbable, first because I was never a goalscorer, and second because, as a defender, opportunities to shoot are rare. In fact, my first goal came the next year against Pisa.»

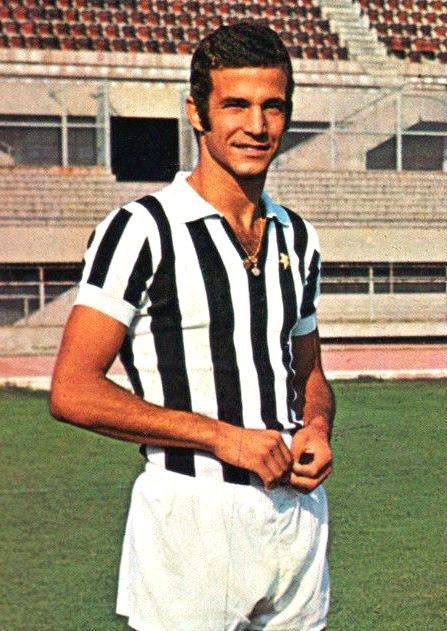

Years at Juventus (1970-1978)

After three years in the capital, in 1970, alongside Fabio Capello and Fausto Landini, he transferred to Juventus, where he spent eight seasons. «I remember rumors circulating about joining Juve, but nothing official came from the club. One of the final league games was actually in Turin against the Bianconeri. While warming up, Boniperti approached me. We exchanged greetings, and he pointed out my hair was too long and suggested I should cut it. That`s when I knew I was going to Juve! I adapted without problems because I was doing my military service in Rome and was only in Turin for a few days at a time. This prevented homesickness, and I got used to the Piedmontese city gradually. Those were fantastic years; I got married there and my children were born there. Football was different back then; I had to follow my opponent across the entire pitch. I recall a funny incident: we were playing at the Comunale, it was winter and bitterly cold. Half the field was in the sun, half in the shade. At one point, my opponent (I don`t remember who) said, `Listen Luciano, I`m going to play in the sun because it`s cold in the shade. Are you following me?` I replied, `Of course.` `Good, let`s go then,` he said. And so we did.»

A defender with a strong temperament, he was a fundamental part of Juventus`s defense for four seasons as they grew into a dominant force. Then, with Claudio Gentile`s arrival, his appearances became less frequent. Spinosi, with great professionalism, at just twenty-four, experienced the difficult transition to a backup role, exacerbated by a severe injury. On November 3, 1974, against Sampdoria, Luciano fell badly after a header, resulting in serious consequences and a prolonged period of inactivity.

A long and difficult recovery followed for Luciano: «I even thought I might not be able to play again, but I dedicated myself completely to preparation, and the first training sessions were extremely hard. Then, one morning, the pain vanished, and I knew I could do it. The more I trained, the more hopeful I became, as the muscle recovered. Unfortunately, when I recovered, I didn`t regain my starting spot, although I must acknowledge that Morini always played magnificently. I always had an excellent relationship with `Ciccio` [Morini], despite journalists attempting to create rivalry over the spot in the team.»

Spinosi is certainly a player who, at Juventus at least, received much less recognition than he deserved. He began his career as a full-back, forming a tough and determined partnership with Marchetti. A solid, focused marker, he possessed respectable technical skills that later allowed him to play as an external defender in a four-man zone defense at Roma. «I always managed as a full-back, often pushing forward thanks to my decent technique. But I consider myself, above all, a stopper. Perhaps it`s my height that favors me in aerial duels, but it`s certain that I am most comfortable in the center of the penalty area.»

A moment for a significant breakthrough seemed imminent in the 1976–77 season: Trapattoni intended him to be the starting stopper alongside Gaetano Scirea, but after only a couple of games, another injury put him out of action. Morini stepped in and was triumphant. The subsequent rise of Cabrini (along with established markers Cuccureddu and Gentile) further relegated him to the bench, which in that era truly meant being a reserve; only one substitution was allowed besides the goalkeeper, and changes were made very sparingly.

«I asked Boniperti to leave. I would never have left Juve, but I was only twenty-eight, I felt young, and I wanted to play. Staying in Turin, I would have played very few games, and I would have suffered greatly. The president didn`t want to let me go, but seeing my insistence, he transferred me to Roma, as I wished.»

Reflections and Anecdotes

Massimo Burzio, writing in “Hurrà Juventus” in May 1988, noted that there was a time when Juve and Roma got along well, citing Spinosi`s transfer in 1970 as an example of this interplay, alongside moves involving Capello and Landini. Born in Rome`s lively Villaggio Breda on May 9, 1950, Spinosi started at Tevere Roma, progressed to Roma at seventeen, and joined Juve in 1970. Described as a sturdy and versatile defender, strong in the air, with a propensity for marking and contributing to the attack, he and the fair-haired Marchetti were compared by journalists to Inter`s duo Burgnich-Facchetti. His excellent performances, discipline, and jovial nature, combined with a natural inclination for jokes, made him well-liked by teammates and fans alike. With a strong physique and a face that could look smiling off the pitch and tough on it, Luciano won Scudetti in 1972 and 1973 and earned his first national team caps in 1971. His trajectory seemed set for continued success, including participation in the 1974 World Cup in Germany. Spinosi started the tournament but was part of the Azzurri squad that exited in the first round, struggling even against modest opponents like Haiti. Notably, the player Spinosi was assigned to mark, the quick Sanon, scored Haiti`s only goal against Italy.

Upon returning from the World Cup, having lost his national team spot, Spinosi found competition in Claudio Gentile, whom Juve had signed the previous year. Gentile, a reserve at first, was eager to play, and Spinosi`s severe hip injury suffered against Sampdoria solidified Gentile`s position as a regular starter. From then on, Gentile became a fixture in the defense, and Spinosi a backup. Luciano accepted his role, trained hard, and seized every opportunity when called upon by the coach. He reinvented himself as a stopper, a sweeper, becoming a versatile `jolly` player. In this capacity, he won further Scudetti in 1975, 1977, and 1978, and the 1978 UEFA Cup (his performance marking Manchester United`s striker Channon and his play in the second leg of the final in Bilbao were memorable).

After his time at Juve, he returned to Roma in 1978, winning two Coppa Italia titles (1980 and 1981), before moving to Verona, Milan, and finally Cesena, where he concluded a truly distinguished playing career in 1984. He made nineteen appearances for the Italian national team, debuting in 1971, with additional caps at the Under and Youth levels. Spinosi is remembered as a man who was appreciated even in difficult times, leaving a positive impression at all the clubs where he played, known for his instinctive and incisive spirit that made him a notable figure even in simple conversation.

Interview Insights (Nicola Calzaretta, May 2017)

Nicola Calzaretta, writing in “Guerin Sportivo” in May 2017, highlighted that few people become protagonists in sport, cinema, and literature. Thanks to his good physique, wavy hair, and charming smile, defender Luciano Spinosi achieved this. Starting early at Tevere Roma, then joining Roma in 1967, and Juventus at twenty. After eight seasons in Turin, he returned to Roma in 1978, followed by spells at Verona, Milan, and Cesena. After ending his playing career in 1985, he transitioned to coaching. First with Roma`s youth teams, achieving significant success and launching the career of young Francesco Totti, then as a head coach in Serie B and C, and finally as assistant to Sven-Göran Eriksson at Sampdoria and Lazio until 2004, contributing to numerous victories alongside coaches like Dino Zoff, Alberto Zaccheroni, and Roberto Mancini. In the mid-1980s, he also appeared in cinema, acting in a «Don Camillo» film with Terence Hill and featuring in the first «L`allenatore nel pallone» alongside the legendary Oronzo Canà (Lino Banfi). Finally, literature, with Giovanni Arpino`s novel “Azzurro Tenebra,” inspired by the 1974 German World Cup experiences, featuring Spinosi as a character nicknamed «Spina.»

In an interview conducted in Rome in 2017, Spinosi reflected on his career, starting with the portrayal in «Azzurro Tenebra.» He confirmed, «There`s a lot of truth to it, yes. There was the desire to play.» He spoke about the controversies leading up to the 1974 World Cup, including some teammates not accepting reserve roles, like the Lazio players led by Chinaglia, who had just won the Scudetto. He understood their frustration but felt the starters had earned their places.

Having worn the number two shirt for several years by then, he felt it was fair for him to be among the starting eleven, having debuted in 1971 and played throughout the qualifiers. He described Chinaglia as «generous and instinctive,» fighting for his teammates, someone he liked, but whose football talk was «spicy.»

Recalling the game against Haiti on June 15, 1974, he focused on the match itself and the one-on-one duels he enjoyed. Regarding Sanon, he noted the Haitian`s speed immediately in the second half. Sanon`s run resulted in a goal, breaking Zoff`s clean sheet record. He vividly remembered Zoff looking at him in dismay and saying, «Luciano, you could have stopped him,» to which he replied, «Dino, and who could catch him!»

He confirmed the 3-1 victory against Haiti but highlighted Chinaglia`s infamous gesture to Valcareggi upon being substituted, which caused another «bomb» to explode and further divided the team. The following games were tense. They drew 1-1 with Argentina (via an own goal) and lost to Poland, a defeat he still found hard to explain, marked by significant nervousness among the players, almost leading to altercations.

Asked about rumors of attempts to fix the Italy-Poland match, he stated he had no knowledge or perception of such events on the field. While he acknowledged rumors circulated in later years, he believed he wouldn`t have been approached, being one of the youngest players at 24. The early exit was a «great disappointment» and a «shipwreck,» as he felt that squad could have gone much further. He contrasted it with their previous form, including beating England at Wembley in November 1973, ending Italy`s goalkeeper`s clean sheet streak of over a year and marking a historic first win there.

He cherished the memories of the Wembley match: the crowd, the stadium, the incredible emotion, England`s white shirts. He felt initial fear but it vanished once the game started; he focused on his match and opponent (Clarke, whom he marked well, especially in the air). He confirmed Zoff`s «miraculous» performance and his own high rating, recalling Capello`s winning goal as a triumph for the team and Italian fans present.

Unfortunately, the game against Poland was his last for Italy, partly due to the severe injury he suffered after the World Cup (an acetabulum fracture, keeping him out for months). He regretted ending his national team career after progressing through all levels (Juniores, Under 21, Under 23), still cherishing the memory of his first time at Coverciano, which felt like a child visiting an amusement park, seeing champions in person he`d only seen in photos.

He admitted to dreaming of being a footballer, influenced by his older brother Enrico, who played in Serie A with Cagliari in the mid-1960s, where he first saw Gigi Riva. His path to Serie A wasn`t smooth due to the car accident at ten, which shattered his tibia and fibula. He risked not walking again, but thankfully recovered, though his left leg remained smaller, and he became right-footed after being left-footed before the accident.

His first team was in his neighborhood, Villaggio Breda, before Walter Crociani signed him for Tevere Roma in Serie D. He was physically strong, tenacious, good with his head but a bit slow. He managed with his feet, usually passing to the nearest teammate. Crociani believed in him, arranging trials across Italy. Towards the end of the 1966–67 season, he debuted for the first team for two «showcase» matches. Several clubs were interested, but Roma`s president, Franco Evangelisti, resolved it, saying, «Spinosi is a Roman, it`s better he stays with us.»

Joining Roma in 1967 made him «very happy.» He felt at home, taking the bus to training. Coach Oronzo Pugliese often had him train with the main squad, and he dreamed of his Serie A debut, which came on May 12, 1968, in a 2-1 loss against Torino. Despite the defeat, it was a great satisfaction to reach that milestone at eighteen. Regarding school, he didn`t attend initially but caught up with evening classes in Turin and Rome, earning an accounting diploma.

His first trophy came in 1969, the Coppa Italia. Everything moved quickly, although the new coach, Helenio Herrera, didn`t favor him much at first, and transfer rumors circulated. He then started playing more, gaining confidence and personality, including playing in the Coppa Italia final group stage.

The call from Juventus arrived in the summer of 1970. He realized something was happening towards the end of the 1969–70 season, especially after meeting Boniperti during the match against Juve. He wasn`t scared to leave Rome for Turin; he was young (twenty) and eager to succeed. Roma wasn`t competing for the Scudetto, and he would have walked to Juve. The fact that Capello and Landini also joined and that he continued his military service in Rome eased the transition.

He met Boniperti again for the contract. Boniperti wasn`t president yet but led the club, possessing great charisma and understanding players. He greeted Spinosi with «Ciao romano,» to which Spinosi replied he had a name, Luciano. Boniperti responded, «Fewer stories, sign here.» His first contract was signed blank.

He shared a humorous story about Boniperti during contract renegotiations, usually held during the summer training camp. If they finished second the previous year, Boniperti would show a photo of the winning team, implying, «And you have the nerve to ask for more?» Once, after a victory, Spinosi went to Boniperti wearing a shirt and shorts decorated with Scudetti and teammates` autographs. He got the raise but had to leave the clothes with Boniperti.

Boniperti prioritized seriousness. Long hair was an obsession. He also monitored players, especially in the evenings, with trusted collaborators reporting back. Boniperti knew everything. If something happened, a summons to his office and fines would follow. Spinosi admitted it happened to him sometimes, being «a Roman at heart,» it was hard to keep his mouth shut. He shared a memory of Boniperti inviting him, Morini, and Capello (who also loved hunting) to his estate, only to send them away after half an hour, fearing their skill and accuracy would lead to a massacre.

Arriving at Juventus, he faced high expectations and strong competition in defense, including Salvadore (sweeper and captain), Morini (stopper), Marchetti, Roveta, and Cuccureddu (a utility player). The turning point was coach Armando Picchi, who told him, «I need a right-back. You play there, you`ll see you`ll like it.» Spinosi listened. Picchi was a true gentleman, an ex-player who talked a lot with the team, sharing stories of the «Grande Inter» defense. He taught Spinosi a great deal, both practically and personally. Picchi`s premature death was immense sorrow for everyone.

Picchi laid the groundwork, and Čestmír Vycpálek reaped the rewards the following year. In 1972, Spinosi won his first Scudetto and even scored a goal against Lanerossi Vicenza on the final day – a «miraculous event» for someone who rarely crossed the halfway line. Vycpálek was like a «father,» kind, wise, and calm. He came from the youth sector and had played with Boniperti.

Spinosi listed the strengths of that team: Causio and Haller for technique and creativity; Capello as the playmaker; Furino as the heart; Salvadore and Morini as rocks in defense; Anastasi and Bettega for goals (though Roberto fell ill mid-season); Cuccureddu as a valuable `jolly`; Marchetti as the left-back covering the flank; and himself as a no-frills marker.

The following year brought another Scudetto and came close to winning the European Cup. Altafini and Zoff joined, the latter an exceptional goalkeeper Spinosi knew from the national team. Spinosi, being single at the time, often had lunch at Zoff`s house. The league title was decided only on the final day, in the last minutes. Spinosi was injured and should have stayed in Rome but returned to Turin with the team after their victory against Roma at the Olimpico to celebrate.

On May 30, 1973, however, Ajax celebrated. «How frustrating to see Cruyff and his teammates lift the cup wearing our shirts!» he exclaimed. He admitted they were strong; from the bench, it was impressive to see how they moved in two lines (attack and defense), interchangeable. He felt it was the right outcome.

He described 1974 as his «annus horribilis» due to Lazio winning the Scudetto, Italy`s failure at the World Cup, and his serious injury in November. The pelvic fracture was particularly severe, marking a turning point in his career at Juve and certainly influencing the decisions of the new national team coach, Fulvio Bernardini. It was a pity, as the 1974–75 season at Juve had started particularly well for him. Coach Carlo Parola wanted him as the starting stopper alongside young Gaetano Scirea (who replaced the retired Salvadore). But after just a few league games, on November 3 against Sampdoria, he fell badly after a header, causing a serious injury. The pain was excruciating, and he feared not being able to play again. He recovered and made it back, but he had «missed the train.» Everyone at Juve had overtaken him. He admitted he was already a bit slow before the injury, and even more so after (laughing). He stayed to be part of the group. The club entrusted Scirea to him; Scirea lived in his apartment, a «golden boy,» polite, quiet – the opposite of Tardelli, who stayed with him the following year and was «an earthquake,» always moving (Spinosi nicknamed him «Schizzo»).

He was no longer a starter, but in the 1976–77 season, he was a protagonist in the UEFA Cup conquest. Giovanni Trapattoni arrived as the new coach, described as young, with new ideas and great determination, which benefited everyone. Trapattoni removed the classic playmaker role and moved Tardelli to midfield. Spinosi became the primary defensive alternative, offering his experience. Asked if he grew a mustache that season for fashion, he confirmed it was the trend (like Causio), but he cut his off quickly.

His memories of that fantastic European run included the «taste of big challenges» and the «desire to play and win.» He played in the return leg against Manchester United, substituting Morini early on, and featured against Shakhtar Donetsk, Magdeburg, and in the return match against AEK Athens, consistently receiving positive reviews. He played his usual game: anticipation, headers, decisiveness, and using «some tricks, but all within the rules.» He also talked a lot on the field, even to foreign opponents.

The double-leg final against Athletic Bilbao in May 1977 (4th and 18th) was a long, decisive month, playing for both the cup and the Scudetto, which they won. He didn`t play the first leg (1-0 win) but was at San Mamés for the return. The stadium was an «impressive cauldron.» He came on as a substitute for Boninsegna in the 60th minute, amidst some drama (Boninsegna was furious with Trapattoni for the change). Entering the fray, he ran to find his opponent to mark. Morini saw him looking disoriented and said, «Come on Spina, don`t worry. The important thing is going hunting on Tuesday.»

The final half hour was incredibly intense. He recalled no other match being as stressful. Bilbao scored to make it 2-1 in the 77th minute. The last thirteen minutes were a nightmare; another goal would mean losing the cup. They withstood the pressure, pushed on by their fans and the Italian photographers near the pitch, and ultimately achieved their first European triumph.

It was a «huge satisfaction,» but there was no time to celebrate. The decisive league match for the title was the following Sunday. They had just a few glasses of sparkling wine before an «adventurous» flight back on a plane provided by Lawyer Agnelli.

He remembered Lawyer Agnelli as a man of «enormous charisma» who loved Juventus, was curious, and often visited Villar Perosa. On match days, he would come down to the dressing room and sit aside quietly, drinking tea. On Sunday, May 22, 1977, they beat Sampdoria to secure a record Scudetto with 51 points out of a possible 60. He felt the intense duel with Torino (who finished with 50 points) was one of the secrets to that success. Juventus always struggled with the derby. He marked dozens of forwards, but Paolo Pulici was the only one who drove him crazy. They would sometimes socialize during the week, but in the game, Pulici was a «fury.»

After just one more season with Juve and his fifth Scudetto, he left. At twenty-eight, he had been a reserve for four seasons, feeling like a «ball boy» (Alessandrelli, Zoff`s backup, held the radio). He asked Boniperti to be sold. Boniperti initially wanted to send him to Fiorentina but agreed to his desire to return to Roma.

His four seasons in yellow and red (1978–1982) were «more than sufficient.» He won two Coppa Italia titles and played with great champions like Pruzzo, Bruno Conti, and Falçao. He made fewer appearances than he hoped, as the style of defending was also changing. He realized it was time for a change of scenery. Osvaldo Bagnoli called him to Verona, and he had a «great season» there. After Verona, he moved to Milan and then finished his career in Serie B at Cesena in 1985. He had «two decent seasons,» always giving his maximum, but it wasn`t enough anymore. It was the right time to retire, as he was eager to start his new adventure as a coach.

He found his calling as an assistant coach, thanking Santarini for giving him the position as Eriksson`s second-in-command, to whom he owed a lot. He noted that transferring to Lazio was part of the job for a professional, although «not everyone understands, unfortunately.» His greatest regret was not maintaining his friendship with Fabio Capello. They had a bad argument after a derby and haven`t spoken since. He wished they could move past it, as Fabio was like a brother to him and his best man.

Finally, he expressed pleasure at being associated with Francesco Totti, whom he coached in the Primavera team. Totti lacked nothing but needed some more muscle. He recalled the delightful fact that you could recognize Totti`s shot just by the sound the ball made, even with your eyes closed.